Changes happen every day on high hazard sites. A valve gets swapped. A control setpoint is nudged. A maintenance routine is shortened because the team is stretched. A temporary bypass stays in place “just for this run”. None of these feel dramatic in the moment, right?

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: incidents rarely come from the change itself. They come from the unmanaged side effects of change. The knock-on impacts that quietly weaken your control barriers until one day, a normal upset becomes a serious event.

That is exactly why Management of Change (MoC) is a major element of Process Safety Management (PSM). Done well, it is not red tape. It is a practical system that asks one simple question:

“What else does this change affect, and have we controlled the risk before we implement it?”

Let’s break down what MoC really is, why it matters, what Texas City taught the industry, and how to make MoC risk based and workable in the real world.

Why MoC Sits at the Heart of Process Safety Management

If PSM is your overall safety engine, MoC is the clutch. It controls how you shift gears without stripping the gearbox.

The difference between “change” and “risk”

Not every change creates new hazards. But many changes alter the conditions that your safety case relies on. That might mean:

- A barrier is no longer reliable (for example, proof testing frequency reduced)

- A hazard is introduced (for example, different chemical cleaning agent)

- A risk increases (for example, higher throughput, higher temperature, different operator workload)

MoC exists because people are great at seeing the obvious parts of change and not so great at spotting second order effects. It is human nature. We focus on the task in front of us.

MoC as a barrier, not a form

A strong MoC process is a control barrier in its own right. It prevents unmanaged risk from entering the system. The paperwork is not the barrier. The thinking is.

When MoC turns into a box ticking exercise, it stops protecting you. It becomes something people avoid. And that is when the cracks appear.

What Texas City 2005 Taught the World

The Texas City refinery disaster in 2005 is often referenced for a reason. It is a real world reminder that process safety can be undermined by decisions that look unrelated to process operations.

When organisational change becomes a process safety hazard

At Texas City, MoC was required for changes except those that were organisational in nature, such as budget cuts.

That is a huge gap. Because organisational changes can directly affect process safety performance. If you cut budgets, you might cut:

- Mechanical integrity inspection scopes

- Maintenance routines and staffing levels

- Training time for operators and supervisors

- Time available for proper pre start up checks

- The depth of peer review and technical assurance

In other words, you can weaken multiple barriers without touching a pipe.

Overdue actions, unapproved changes, and hidden risk

One of the most common failure patterns in major incidents is this trio:

- Actions from previous MoCs not closed out

- Changes implemented before final approval

- A growing backlog that normalises risk

It is like driving a car where the dashboard warning lights have been on for months. You stop noticing them. Then something fails.

A simple lesson: control barriers do not maintain themselves

Barriers need attention, time, and resourcing. If your MoC system does not treat resource and organisational changes as risk relevant, the system can look “compliant” while safety is quietly degrading.

What Counts as a Change (and What Often Gets Missed)

Ask ten people what counts as a change and you can get ten different answers. That is why MoC needs clear triggers.

Like for like replacements versus “close enough”

A key principle is this: anything not like for like must be assessed.

“Like for like” is narrower than people think. It is not “same size and fits the flange”. It is more like:

- Same material specification

- Same pressure rating

- Same performance curve

- Same control philosophy and fail position

- Same hazardous area classification compliance

- Same inspection and maintenance requirements

If any of those differ, it is not like for like. It is a change.

Process changes, maintenance changes, and operating changes

MoC is not only for big capital projects. It should catch everyday change such as:

- New operating limits or setpoints

- Different start up or shutdown sequences

- Changes to alarm settings or trip values

- Modified cleaning regimes (CIP, chemical strength, temperature)

- Altered inspection frequencies or deferrals

- Swapped suppliers for critical spares

Temporary changes that quietly become permanent

Temporary changes are notorious. They often start with good intent:

“Just bypass this for a week until the new part arrives.”

Then weeks turn into months. The site gets used to operating with a weakened barrier. The bypass becomes invisible.

A mature MoC process includes temporary change and forces periodic review and reassessment for continuation.

The IChemE Principles for Effective MoC

IChemE recommendations can be boiled down into practical habits that separate strong MoC systems from weak ones.

Anything not like for like must be assessed

This is the line in the sand. If your MoC process is unclear here, you will miss changes. And missed changes are often the ones that hurt you.

Review MoCs and drive actions to closure

An MoC is not complete when it is raised. It is complete when the actions are closed, verified, and embedded.

If you have overdue actions, the system is telling you something important: either MoC is under resourced, or actions are not owned, or the process is too clunky. Sometimes all three.

Use leading and lagging KPIs to measure effectiveness

If you do not measure MoC performance, you are guessing. And process safety is not a place for guessing.

Leading KPIs tell you where the next failure might come from. Lagging KPIs tell you what has already gone wrong.

Include temporary change and reassessment

Temporary changes need an expiry date, a review cadence, and clear criteria for extension. Otherwise, “temporary” becomes a loophole.

Review, peer review, and authorise before implementation

This is not about bureaucracy. It is about forcing the right questions before the change becomes real.

Peer review is especially important when people are under pressure. When the site is busy, people rush. A second set of eyes slows the rush down just enough to catch what matters.

Common Failure Modes We See in Real Sites

If you want to improve MoC quickly, focus on the patterns that repeatedly show up.

The “paper MoC” problem

Some sites have MoC procedures that look great but live in binders, not in daily work. People raise MoCs after the change, or not at all, because it feels like admin.

The fix is not more paperwork. It is simpler workflows, clearer triggers, and leadership that rewards early escalation.

Approval after the fact

If a change is implemented and then “back approved”, your MoC system has become a diary, not a barrier.

This often happens because MoC is too slow. People do not have time to wait. That is a design issue. A good MoC process has fast routes for low risk change and deeper review for higher risk change.

Weak link between MoC and mechanical integrity

If MoC can reduce inspection frequencies or defer work without process safety review, you are gambling with barrier health.

Mechanical integrity is not a nice to have. It is one of the foundations of major accident prevention.

Contractor and supplier driven changes

Suppliers substitute components. Contractors suggest alternatives to meet programme. These changes can be totally reasonable, but only if they are assessed through the MoC lens.

If your MoC process does not capture third party driven changes, you are leaving a big gap.

A Risk Based MoC Approach That Matches Your Site

Not every site needs the same MoC depth. A small batch plant is different from a COMAH top tier facility. That is why MoC should be risk based.

Scaling MoC to the scope, complexity, and hazard

A risk based MoC approach should scale with:

- The hazard severity of the system affected

- The complexity of the change

- The novelty of the operating conditions

- The potential impact on existing control barriers

- The competence required to review it properly

Minor, moderate, and major change categories

A practical approach is to categorise changes into tiers, for example:

- Minor change: like for like confirmed, low consequence, no barrier impact

- Moderate change: some technical differences, potential barrier impact, requires peer review

- Major change: affects hazardous scenarios, operating limits, safeguards, or safety case assumptions, requires formal hazard review and higher level authorisation

Who must review and who must approve

This is where MoC becomes real. Define roles clearly, such as:

- Originator: explains the change and the reason

- Discipline reviewers: process, mechanical, EC&I, operations

- Process safety reviewer: checks barrier impact, hazard assessment, and actions

- Approver: accountable leader with authority to accept the residual risk

No clarity here equals delays and frustration. Clarity makes the system faster.

Making MoC Practical, Fast, and Hard to Bypass

MoC should feel like a guardrail, not a roadblock.

Clear triggers and decision trees

People should not have to guess whether they need an MoC. Give them a simple decision tree. For example:

- Is it like for like in spec, performance, and duty

- Does it affect operating limits, alarms, trips, or procedures

- Does it affect mechanical integrity, inspection, testing, or maintenance

- Does it affect hazardous area compliance or relief protection

- Does it affect staffing, competence, or supervision levels

If yes to any, raise an MoC.

Defined roles and accountability

MoC fails when everyone thinks someone else is responsible for closing actions. Assign owners and dates, and make overdue items visible.

Integrating MoC into the way work happens

MoC should connect with:

- Work management and permit systems

- Maintenance planning and deferral processes

- Document control for P&IDs, operating procedures, and cause and effect charts

- Training and competency updates

- Pre start up safety review for higher risk changes

When MoC is integrated, it stops being optional.

Metrics That Actually Tell You If MoC Works

When we embed MoC into PSM systems for clients, we include metrics that can be used, not just reported.

Leading KPIs that predict trouble early

Examples of useful leading KPIs include:

- Number of overdue MoC actions

- Percentage of temporary changes past review date

- Average time from MoC raised to approval by category

- Percentage of MoCs with documented barrier impact review

- Percentage of changes captured versus audit identified changes

- Number of emergency changes and their root causes

Lagging KPIs that reveal systemic gaps

Lagging indicators might include:

- Incidents where change was a contributing factor

- Near misses linked to undocumented change

- Audit findings related to MoC compliance

- Equipment failures linked to altered maintenance regimes

Turning KPIs into action, not dashboards

KPIs are only useful if they drive decisions. If you track overdue MoC actions but do not resource closure, the metric becomes noise.

A good rule is: if a KPI trend worsens, it should trigger a management discussion and a corrective plan.

MoC and Safety Leadership: The Real Multiplier

Procedures do not create safety culture. People do. Leadership is what turns MoC from paperwork into protection.

Buy in beats bureaucracy

When leaders ask “have we assessed this change?” and mean it, MoC becomes normal. When leaders bypass MoC to save time, everyone learns that production wins. And that lesson sticks.

Coaching supervisors to spot change

Supervisors are the frontline of MoC success. They see small changes first. Training them to recognise change triggers and escalate early is one of the highest value improvements you can make.

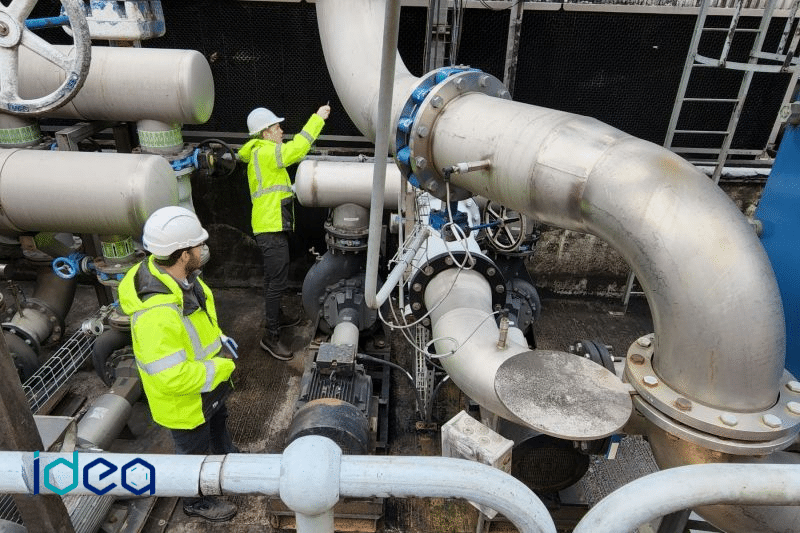

How IDEA Supports Clients with MoC and Process Safety Management

At IDEA, we take a risk based approach to MoC that aligns to the scale, scope, and complexity of the process under consideration.

Building MoC into a complete PSM system

MoC is strongest when it is part of a complete PSM framework that includes:

- Process hazard analysis and safeguard management

- Mechanical integrity and inspection planning

- Operating procedures and training

- Incident investigation and learning

- Audit and assurance

Pragmatic procedures, templates, and training

We help clients develop MoC procedures that people will actually use, including:

- Simple MoC triggers and decision trees

- Proportionate risk assessment routes

- Clear approval and peer review structures

- Templates that are short, structured, and focused on barrier impact

- Training for operators, supervisors, and engineering teams

Audits, assurance, and continuous improvement

We also support:

- MoC audits and health checks

- Backlog and overdue action recovery plans

- KPI frameworks that measure MoC effectiveness

- Leadership coaching on what “good” looks like on site

Strengthen Your MoC Before the Next Change Tests You

Changes will keep coming. The real question is: are you confident your site is catching the changes that matter and controlling the risk before implementation?

If you want to improve your MoC process, reduce bypass behaviour, and embed meaningful metrics into your PSM system, IDEA can help.

Contact IDEA to arrange a practical MoC and PSM review, tailored to your site and hazards. We will help you identify gaps, simplify the workflow, and build a system that protects your barriers without slowing your operation.

Conclusion

Management of Change is one of those process safety elements that only gets attention when something goes wrong. But when MoC is done properly, it quietly prevents the wrong things from happening in the first place. It captures change, assesses barrier impacts, drives actions to closure, and builds confidence that your safety case still stands after the dust settles. The lesson from Texas City is clear: even organisational decisions can weaken barriers if they are not managed as risk relevant changes. A risk based MoC approach, backed by practical triggers, peer review, and meaningful KPIs, is one of the most effective ways to protect people, assets, and reputation in high hazard environments.

FAQs

1) What is the difference between MoC and a risk assessment?

MoC is the management system that controls how changes are proposed, reviewed, approved, implemented, and verified. Risk assessment is one part of MoC, used to evaluate hazards and barrier impacts for a specific change.

2) Does MoC apply to temporary changes?

Yes. Temporary changes should be included, tracked, and periodically reviewed. They should have an expiry date and clear rules for extension or removal.

3) What counts as like for like?

Like for like means the replacement matches the original specification, duty, and performance in a way that does not change the hazard or barrier assumptions. If material, rating, performance, or function differs, it is not like for like.

4) Why do MoC actions become overdue so often?

Common reasons include unclear ownership, lack of resourcing, too many low value MoCs clogging the system, and weak governance. A risk based MoC structure and clear accountability usually reduce backlogs quickly.

5) What are good leading KPIs for MoC?

Useful leading KPIs include overdue MoC actions, temporary changes past review date, time to approve by change category, and the percentage of MoCs with documented barrier impact review.