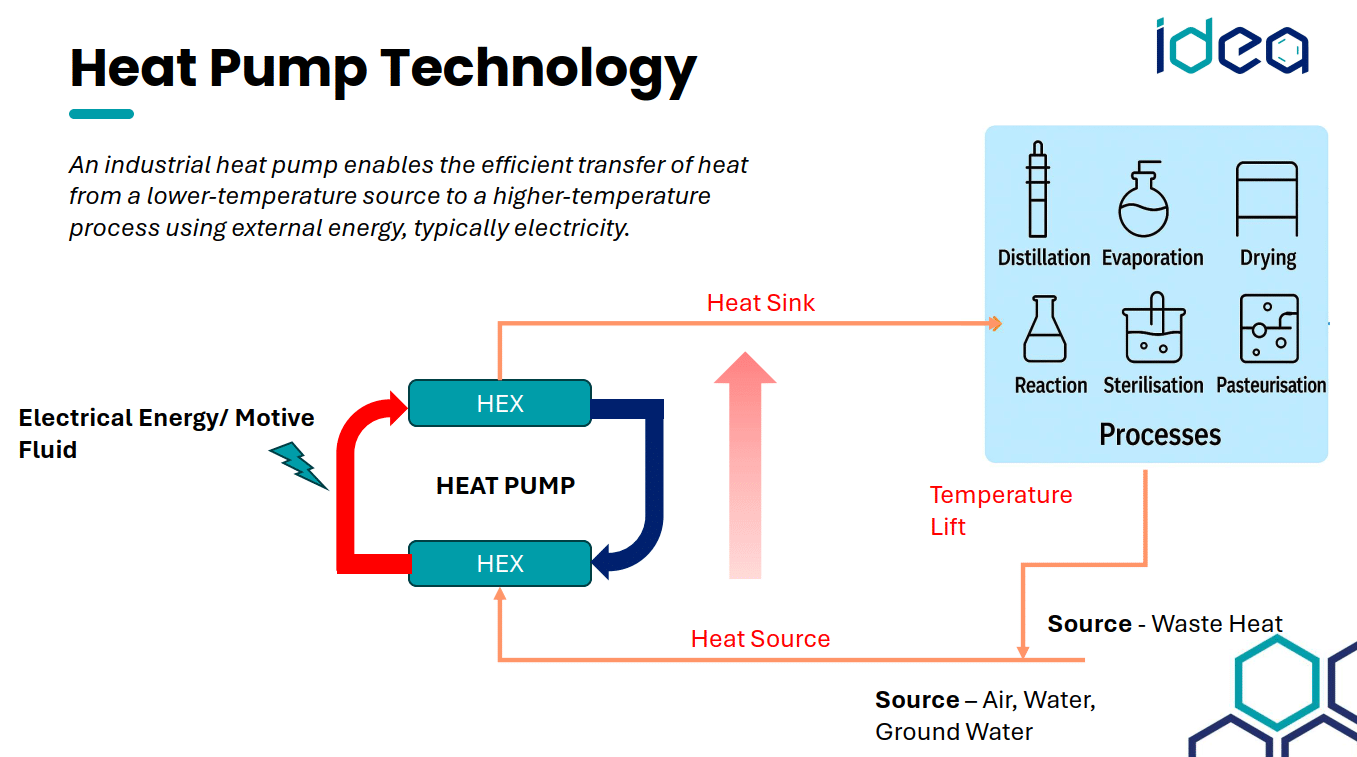

Introduction – Why Heat Source and Sink Mapping Matters

Thinking about industrial heat pumps but not sure where to plug them in? You’re not alone.

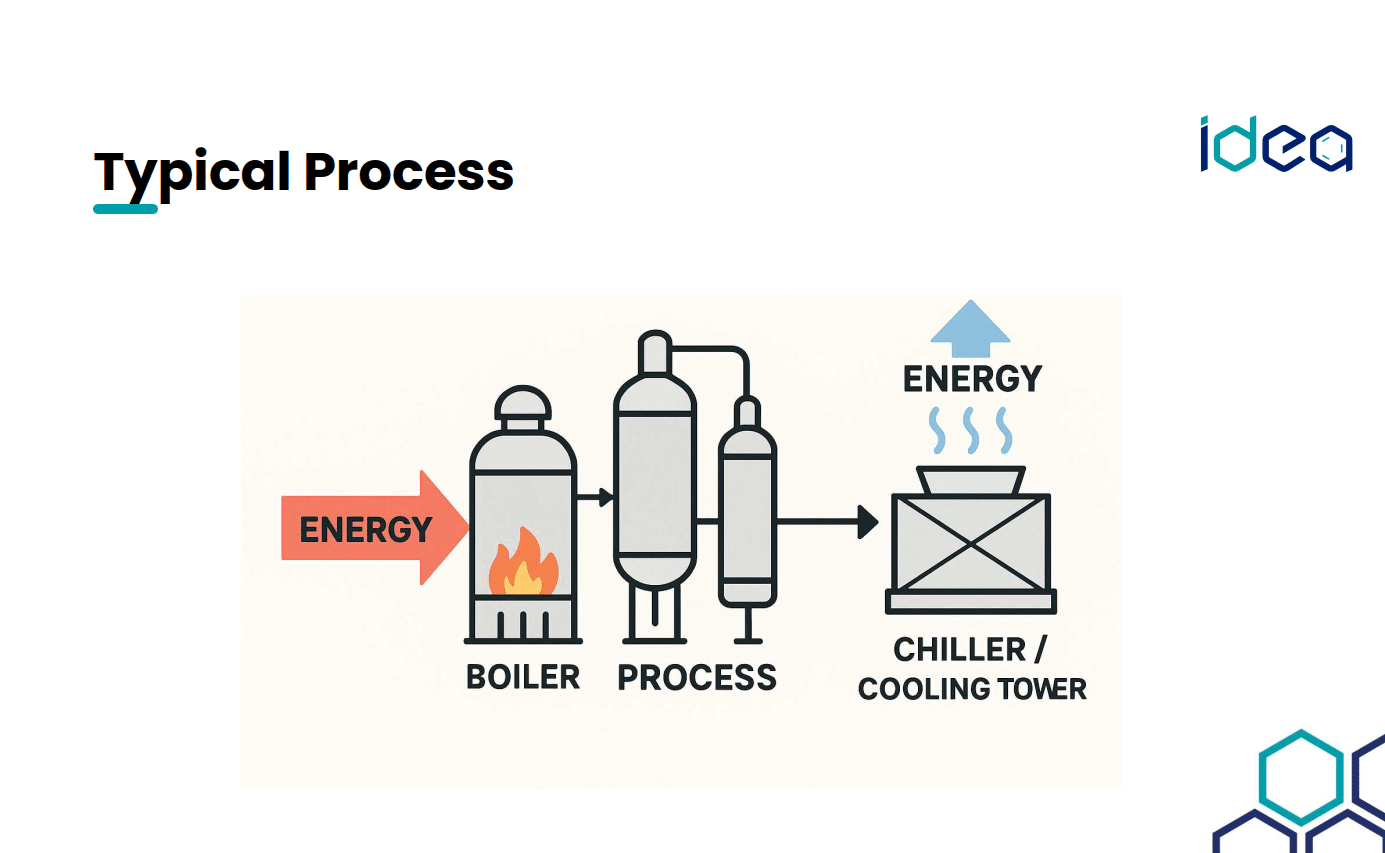

Most process sites already have what they need for a great heat pump project: plenty of warm “waste” streams (heat sources) and lots of medium-temperature users (heat sinks). The challenge is seeing the plant not as a collection of isolated systems, but as one big energy ecosystem.

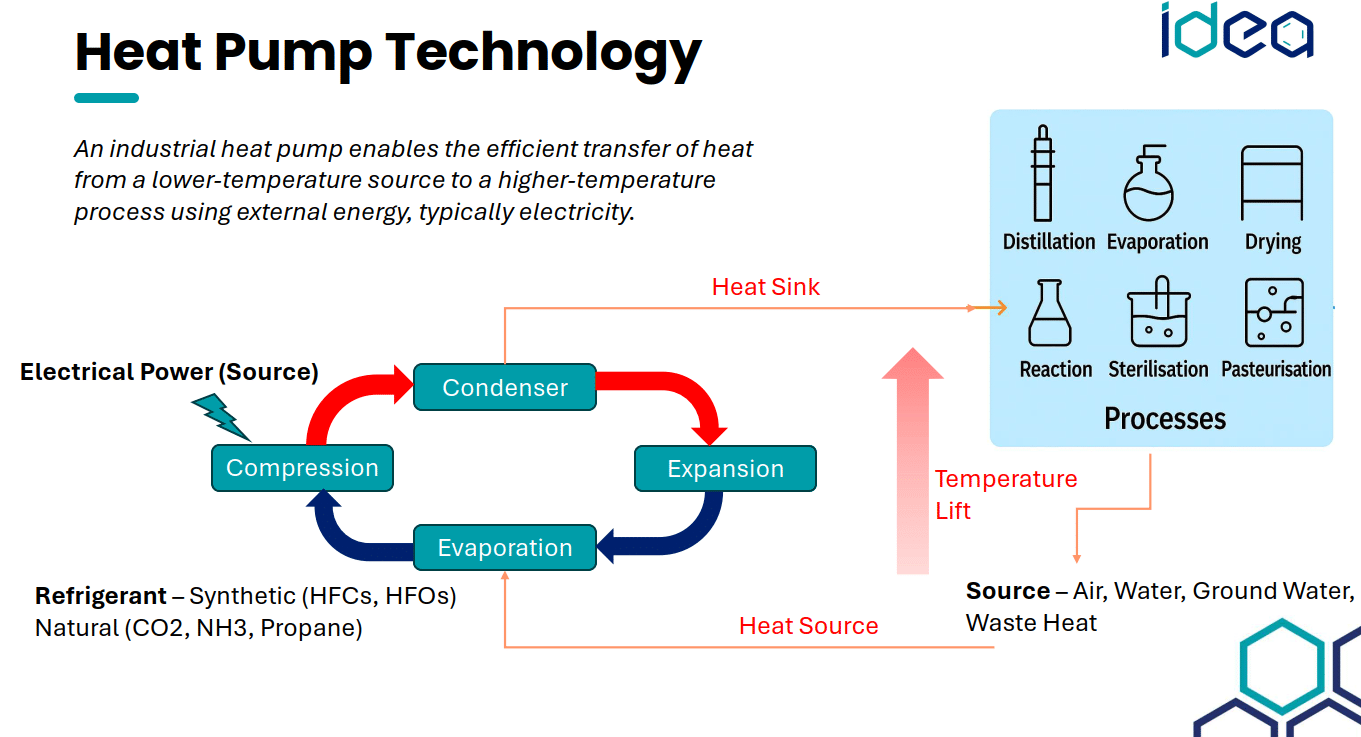

Industrial heat pumps sit right in the middle of that ecosystem. They lift heat from “too cool to be useful” to “just hot enough to replace steam or direct fuel”. To do that sensibly, you need a clear view of:

- Who wants heat? (heat sinks)

- Who’s throwing heat away? (heat sources)

- At what temperatures and loads?

Let’s walk through how to identify both, using real examples from evaporators, distillation, drying, pasteurisation, hot water systems, reactors, utilities and more.

Core Concepts – Heat Sinks, Heat Sources and Temperature Levels

What is a heat sink in process plants?

A heat sink is any duty where the plant is demanding heat:

- Steam to a reboiler

- Hot water to a bottle washer

- Heating loop to a reactor jacket

- Hot air to a spray dryer

In design terms, heat sinks show up as steam loads, hot water loads, thermal oil duties or hot air/gas duties. For heat pump projects, we’re especially interested in sinks in the 60–140°C range, where modern high-temperature heat pumps can realistically operate.

What is a heat source in process plants?

A heat source is any stream where heat is being rejected to ambient or to a utility:

- Refrigeration condenser water headed to a cooling tower

- Warm cooling water returning to a cooling tower

- Hot product being cooled down before storage

- Warm wastewater going to drain

If you’re currently spending money to cool something down (fans, cooling towers, chillers), that’s a strong candidate as a heat pump source.

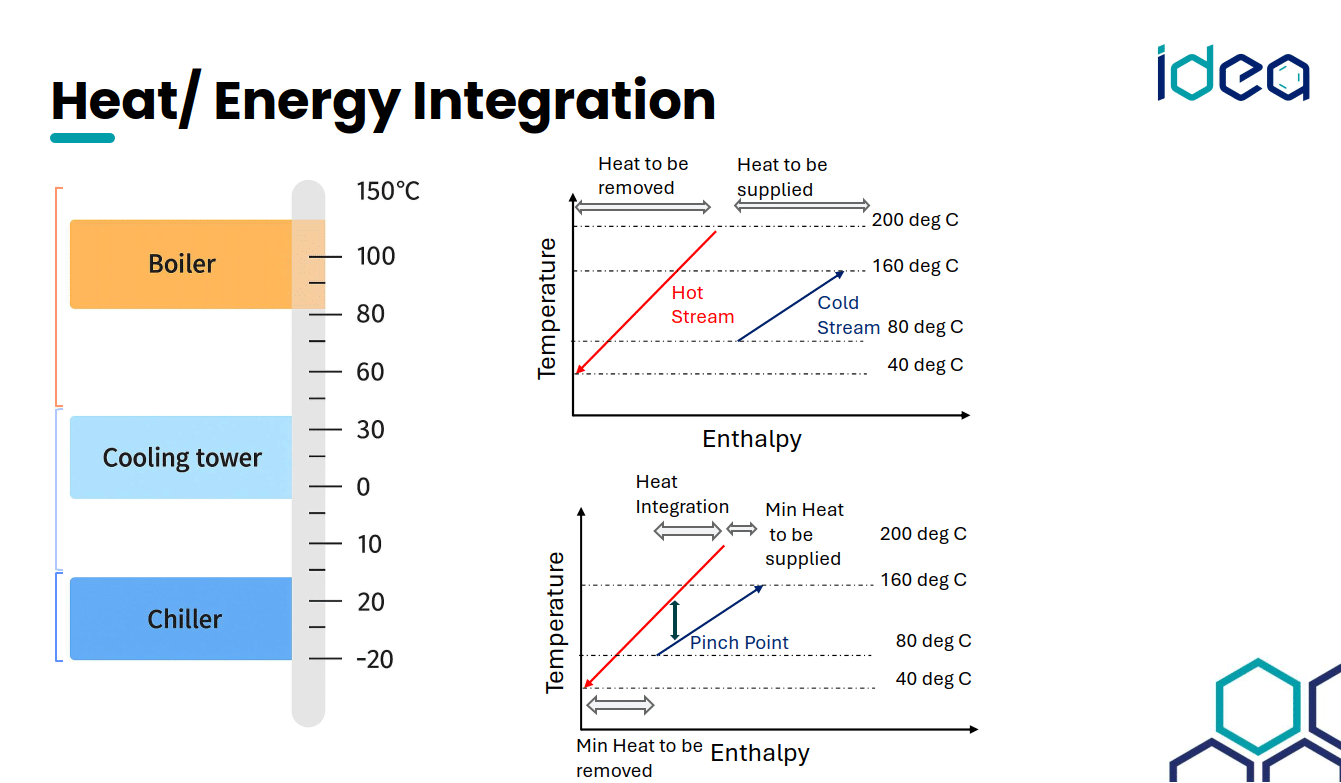

Temperature lift, ΔT and practical limits

Industrial heat pumps aren’t magic. They work best when:

- Source temperature is reasonably warm (say 10–40°C)

- Sink temperature is not too high (say up to 90–120°C, depending on technology)

- Temperature lift (ΔT) is kept sensible (typically ≤40–50 K for good efficiency)

So as we go through sinks and sources, keep these questions in mind:

- How hot does the sink really need to be?

- How warm is the potential source?

- Can you tighten approach temperatures with good heat exchanger design?

Step-by-Step Approach to Mapping Heat Sinks

Before diving into the giant list, it helps to have a simple method.

Start from the steam balance and hot water users

Grab your site steam and hot water balance. You’ll usually see big lumps of demand for:

- Reboilers

- Pasteurisation and hygienic heating

- Hot water systems

- Space heating

These are your primary heat sinks. Highlight anything in the 60–120°C range – these are prime candidates for heat pump supply instead of (or alongside) steam.

Look at batch vs continuous loads

Some loads are continuous (evaporators, continuous dryers, some distillation columns).

Others are batchy (CIP, batch reactors, certain washers).

Heat pumps love steady loads but can still support batch loads with:

- Buffer tanks

- Smart controls

- Hybrid operation with existing boilers

Mark which sinks are continuous and which are batch to understand how to size and control your system.

Prioritise large, steady, medium-temperature sinks

As you create your “sink list”, rank them by:

- Annual energy use (MWh/year)

- Typical temperature level

- Load profile (continuous vs batch)

The top of this list is where your future heat pump is most likely to land.

Key Heat Sinks in the Process Industry

Evaporation & Concentration Systems

These duties are often huge energy consumers and often rely on steam.

Single / Multiple-Effect Evaporators

- Used in food, chemicals, wastewater concentration, etc.

- Reboiler or calandria usually powered by steam.

- Typical heating media: 80–130°C.

Heat pump opportunity:

Supply part or all of the heating duty with hot water or low-pressure steam generated by a high-temperature heat pump, especially if you already have warm condensate or vapour streams.

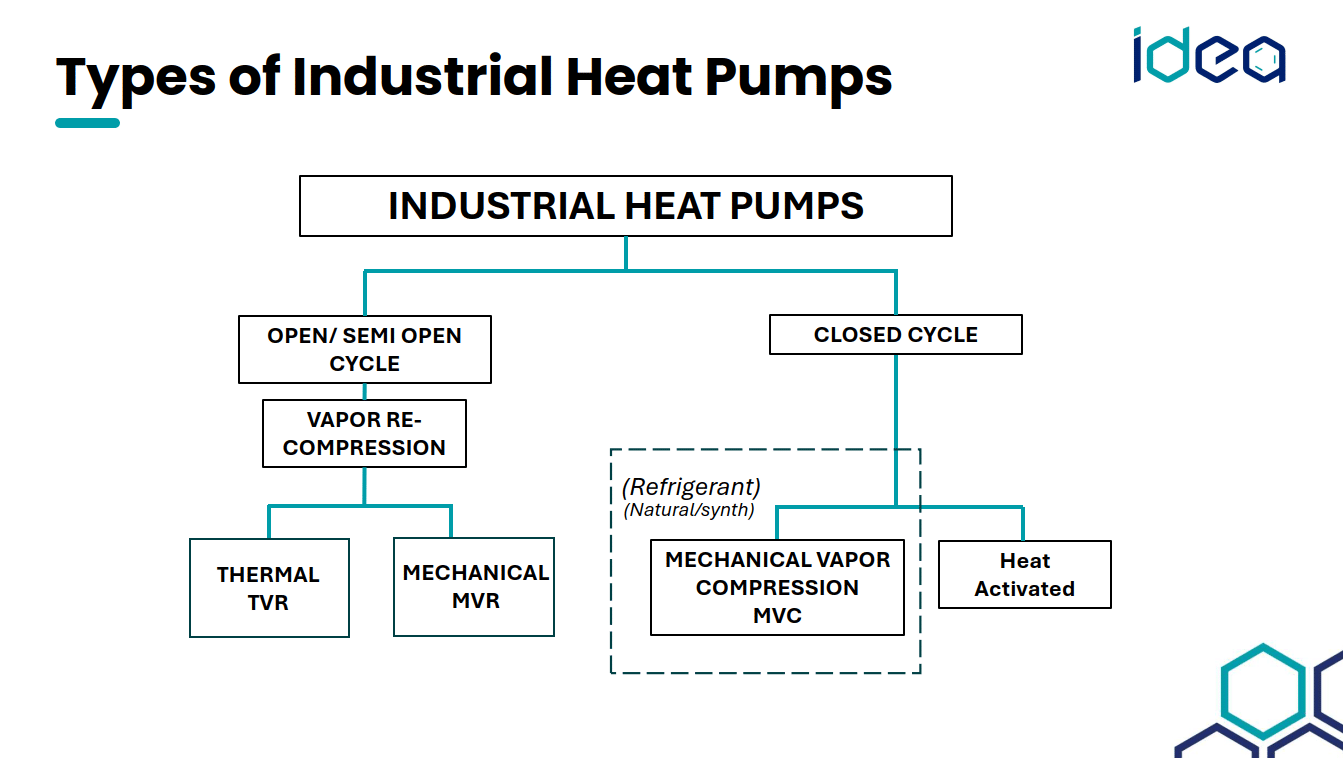

MVR / TVR-Assisted Evaporators

- Mechanical vapour recompression (MVR) and thermocompression (TVR) already reuse vapour.

- Still often require top-up steam for start-up or certain steps.

Heat pump angle:

When MVR runs, there can be warm condensate and vapour that can feed a heat pump for auxiliary duties (e.g. preheating feeds or other sinks).

Crystallisers

- Often operate at specific temperatures and use jacket/wall heating or external loops.

- Energy-intensive when concentrating solutions.

A heat pump can support jacket heating loops or slurry preheaters if the required temperature is within the heat pump’s range.

Distillation & Separation Systems

Distillation is almost synonymous with “steam bill”.

Column Reboilers (Kettle, Thermosiphon, Forced Circulation)

These reboilers:

- Commonly run with LP steam (e.g. ~3–6 barg)

- Provide stable, continuous heat sinks

Heat pumps can either:

- Directly supply hot water to an intermediate loop, or

- Generate low-pressure steam via a secondary heat exchanger.

Side Reboilers / Strippers

Side draws and strippers often have:

- Slightly lower temperature duties

- Variable loads

They’re good candidates for secondary or peak-shaving heat pump duties.

Distillation Feed Preheaters

Preheating feeds reduces reboiler duty. The preheater itself is a heat sink that might accept hot water from 70–110°C.

Rectification / Absorption / Stripping Columns

Anywhere you see:

- Reboil duties

- Condensing & reflux duties

you have paired sinks and sources. This is perfect for integrated heat pump concepts (heat from condensers upgraded to serve reboilers).

Drying Systems

Dryers are gas- and steam-hungry and generate hot, humid exhaust – a dream for heat pumps.

Spray Dryers

- Need hot air, often 150–250°C at inlet.

- Not all of this can be achieved by heat pumps, but…

Heat pumps can:

- Preheat inlet air up to, say, 80–120°C, reducing gas or steam firing.

- Recover heat from exhaust air and recycle it into preheating or hot water systems.

Fluidised Bed Dryers

Similar story:

- Large airflows

- Elevated temperatures

- Exhaust streams that can feed heat pumps

Belt / Tunnel / Tray Dryers

- Often use hot water or steam coils.

- Temperatures may be moderate enough for direct heat pump supply.

Drum / Rotary Dryers

Can be more challenging due to high temperatures and dusty, fouling exhaust – but the exhaust gas is still a potential heat source.

Desiccant Dryer Regeneration Heaters

- Regeneration air typically 80–140°C.

- A good match for modern high-temp heat pumps.

Pasteurisation, Sterilisation & Hygienic Heating

Food, drink and pharma are full of hygienic heat sinks.

Plate / Tubular Pasteurisers

- Product heated to 60–90°C.

- Usually heated with hot water or steam.

Heat pumps can:

- Generate hot water loops at 75–90°C to supply pasteurisation.

- Recover heat from the cooling side of the pasteuriser as a source.

UHT / HTST Systems

For higher temperatures (e.g. above ~120°C), heat pumps might:

- Preheat product before the final steam-based step.

- Reduce the peak steam requirement rather than replacing it completely.

CIP / SIP Heating Circuits

- Large intermittent sinks for hot water (60–85°C) and sometimes steam.

- Perfect for pairing with heat pump + buffer tank.

Bottle / Keg / Cask Washing Systems

- Multi-stage washers with several temperature zones.

- Heat pump hot water can cover many of these stages, especially the lower-temperature prewash and intermediate zones.

Space Heating & HVAC on Process Sites

This is often the first “easy win”.

LTHW / MTHW Heating Circuits

Low-temperature hot water (LTHW) at 60–80°C is ideal for heat pumps.

Medium-temperature hot water (MTHW) at 80–120°C can be served by high-temperature units.

AHUs with Hot Water Coils

Air handling units:

- Provide space heating and sometimes dehumidification.

- Are a natural heat sink for heat pump-generated hot water.

Production Hall Heating / Dehumidification

Pairing hall heating and dryer/waste heat via a heat pump can:

- Improve comfort

- Reduce gas heater usage

- Integrate nicely with existing HVAC systems

Hot Water & Wash Systems

Hot water is the backbone of many plants.

General Plant Hot Water (60–90°C)

- Showers, wash-down hoses, utility hot water.

- Classic heat pump sink – often continuous or frequent use.

Tank / Vessel / Filter / Centrifuge Washing

These systems:

- Often use hot water or steam for flushing.

- Can shift to heat-pump-fed hot water with minimal process change.

IBC / Tote / Truck Wash Systems

Mobile and container wash systems typically run at 50–80°C – well within heat pump comfort zone.

Laundry / Textile Wash Water

In textile and garment plants, large, stable hot water loads make this a top-tier sink.

Reactor Heating & Cooling Systems

Reactions don’t just need control – they need lots of heat in and out.

Batch Reactor Jackets / Coils

- Frequently switch between heating and cooling duty.

- A heat pump can supply heating via a hot water loop and use reactor cooling return as a heat source.

Continuous Reactor Heating Loops (Water / Thermal Oil)

Where temperatures are moderate, water-based loops can be partially or fully served by heat pumps.

Polymerisation / Specialty Chemicals Reactors

Tight temperature control, often with multi-level heating and cooling. Heat pumps can support preheat and moderate-temperature segments of the duty.

Boiler & Steam System Peripherals

Even within the boiler house, you’ll find sinks.

Boiler Feedwater Preheaters

Raising feedwater from, say, 20–60°C to 80–105°C with heat pumps reduces flue gas losses and fuel use.

Deaerator / Make-Up Water Preheat

Another continuous sink ripe for high-temperature hot water.

Low-Temperature Steam Users

Some tank coils, tracing systems and small users can be replaced by hot water circuits, which are much more heat pump friendly.

Fermentation, Mashing & Cooking Systems (Food & Drink, Bio, etc.)

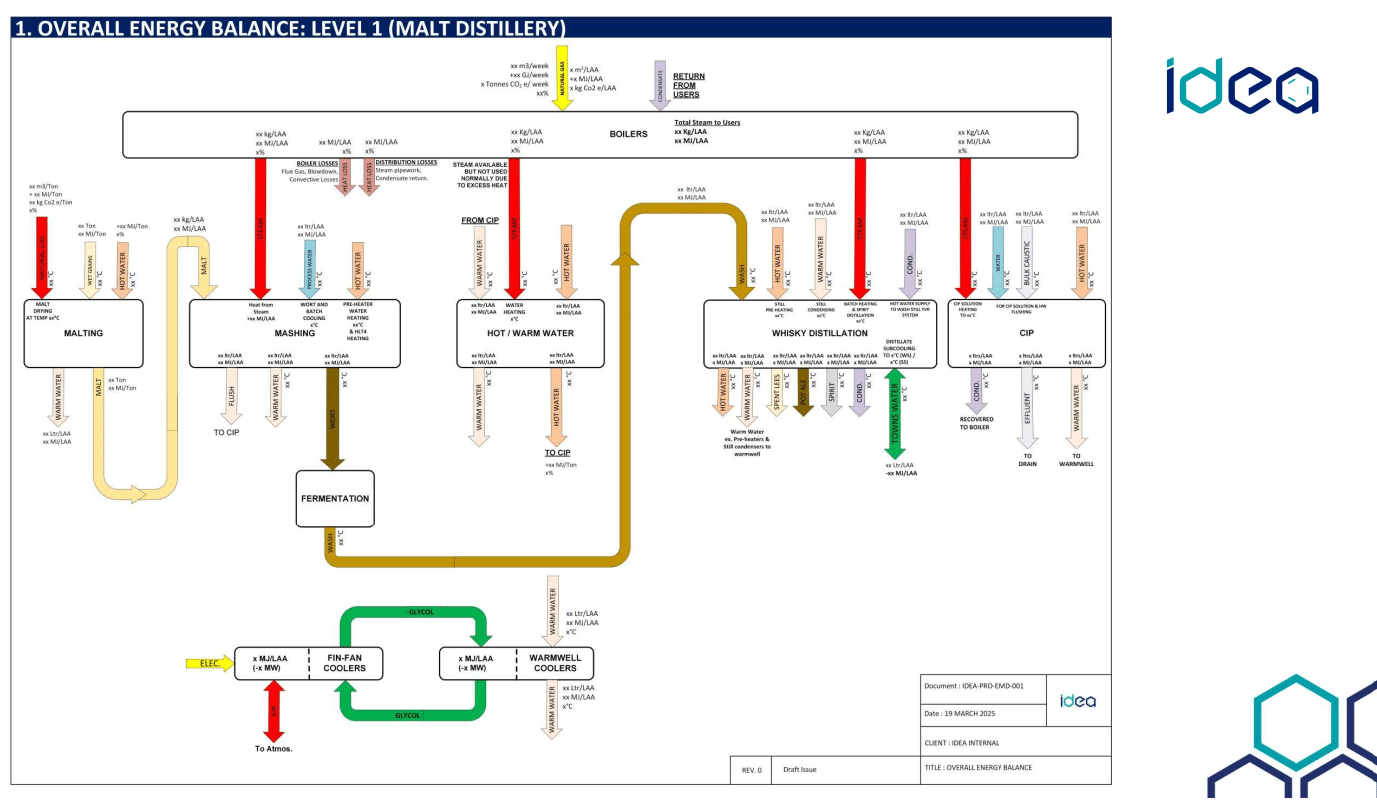

Breweries, distilleries, bio plants – all full of heat sinks.

Wort / Mash Heating and Cooling

- Heating up mash and wort is energy-intensive.

- Cooling again (before fermentation) creates a paired sink and source.

Fermenter Temperature Control

Fermenters are often cooled continuously. The removed heat is a great source. On the heating side, CIP and hot water for cleaning are sinks.

Cooking / Blanching / Scalding Systems

Cooking kettles, blanchers and scalding systems (e.g. meat, veg) typically operate in the 70–100°C range – ideal for heat pump integration.

Wastewater & Effluent Treatment Systems

Don’t underestimate the drain.

Warm Effluent Tanks / Equalisation Basins

- Effluent often leaves process at 25–60°C.

- Using heat exchangers plus a heat pump, this can become a significant heat source.

Anaerobic Digester Heating

Digesters often run at ~35–40°C (mesophilic) or higher. Heating them is a stable, continuous sink.

Sludge Pasteurisation / Drying Support

Where you’re pasteurising sludge or supporting sludge dryers, you’ll see medium-temperature hot water and air loads that can be supported by heat pumps.

Sector-Specific Auxiliaries

Pulp & Paper Hood / Air Systems, Whitewater Heating

- Hood air heating and whitewater heating are major sinks.

- Paper machine exhaust and whitewater cooling are major sources.

Textile Dyeing / Bleaching / Wash Ranges

Multiple wash and dye stages at different temperatures – heat pumps can supply several stages and recover heat from final rinses.

Pharma/Biotech WFI and Media/Buffer Prep Heating

- WFI (water for injection) storage and distribution heating, buffer prep, media prep – all significant hot water loads.

- Demand high reliability and cleanliness but highly compatible with heat pump hot water loops.

Key Heat Sources for Industrial Heat Pumps

Now let’s flip the lens and look at where we’re throwing heat away.

Refrigeration & Chilling Systems

Refrigeration Condenser Heat (Ammonia, CO₂, HFCs)

This is often the largest single heat source on site:

- Condenser water or gas is warm (25–40°C) and continuous.

- Rather than sending it to atmosphere or a cooling tower, feed it to a heat pump.

Chiller Condenser Water (Glycol / Brine / DX Systems)

Chillers serving production rooms, cold stores, process cooling – all produce warm condenser water that’s perfect for heat recovery.

Heat from Cascade Refrigeration Warm Stages

In cascade systems (e.g. CO₂ + ammonia), the intermediate stage is a high-grade heat source that can be upgraded further.

Cooling Water & Closed Cooling Circuits

Cooling Tower Return Water

If you have a cooling tower, you likely have:

- Warm water returning at 25–35°C.

- This is a universal heat pump source.

Process Cooling Water Return (Jackets, Coils, HEX)

All that jacket and exchanger cooling:

- Represents controlled heat removal.

- Can be intercepted via plate heat exchangers and sent to heat pumps.

Closed-Loop Glycol / Tempered Water Circuits

Tempered loops that run at 0–25°C (or higher) and reject heat to dry coolers or towers are excellent sources.

Compressors & Vacuum Systems

Air Compressor Aftercoolers (Instrument Air, Plant Air)

- Air compressors dump a lot of heat into cooling water or air.

- That’s a continuous, predictable source, often at 25–60°C.

Refrigerant Compressor Intercoolers / Oil Coolers

These circuits typically operate at moderate temperatures and steady loads.

Vacuum Pump Cooling (Liquid-Ring, Rotary Vane etc.)

Where water-cooled, vacuum pumps generate warm cooling water that can support smaller heat pump systems.

Process Condensers & Coolers

Column Overhead Condensers (Distillation, Absorption, Stripping)

These units:

- Reject latent heat during condensation.

- Are high-value sources, especially when the condensing temperature is 40–80°C.

Evaporator Condensers (Single/MEE Systems)

Vapour from evaporators condenses at useful temperatures; instead of dumping it to cooling water, use it as a heat pump source.

Product Coolers (Hot Product Before Storage/Packing)

Hot product needs cooling to storage or packaging temperature. That cooling duty is a compact but often continuous heat source.

Flash Condensers / Knock-Out Pot Coolers

Any flash steam or vapour condensing is a goldmine for heat recovery.

Warm Effluents & Waste Streams

Warm Wastewater / Effluent from Process or CIP

CIP and washing systems send large amounts of hot water down the drain.

Plate heat exchangers + heat pumps can convert this into a major heat source.

Blowdown Streams (Boiler, Cooling Tower)

Blowdown is small in volume but high in temperature – good for localised recovery.

Warm Drains from Washing / Cleaning / Bottle-Wash / Keg-Wash

Washers and cleaners send hot water to drain at 40–70°C. Capture it at source before mixing with cold streams.

Low-/Medium-Grade Heat from Utilities

Boiler Feedwater Tank / Deaerator Vents & Surfaces

Radiant and convective losses plus vent heat can sometimes be captured via heat exchangers.

Condensate Return That’s Dumped or Overcooled

If you’re cooling condensate to near-ambient before dumping, you’re literally throwing away ideal heat pump source energy.

Low-Grade Heat from Thermal Oil or Hot Water Return Lines

Return lines at 40–80°C are the perfect inlet to a heat pump evaporator.

Air & Gas Streams

Exhaust Air from Dryers (Spray, Belt, Fluid Bed, etc.)

These are often:

- Hot

- Moist

- Continuous

Use air-to-air or air-to-water exchangers to capture heat and feed a heat pump.

Warm Ventilation / Extraction Air from Process Halls

If you’re ventilating hot production spaces, that air can be a source.

Low-Temperature Flue Gas (Where Fouling Allows Indirect Recovery)

When flue gas is relatively clean and moderately hot, you can use condensing economisers feeding heat pumps to squeeze out more usable heat.

Biogas / Waste-to-Energy Systems

Engine / CHP Jacket Water and Oil Cooler Circuits

CHP units reject massive amounts of heat:

- Jacket water

- Lube oil coolers

- Intercoolers

Heat pumps can lift this to higher temperatures for site use.

Biogas Compressor Intercoolers

These stages add smaller but continuous heat sources.

Effluent / Digestate Streams Leaving Anaerobic Digesters

Digestate at elevated temperature is another potential source.

Ambient & Environmental Sources (Site-Wide)

Ambient Air (Air-Source HTHP)

Air-source heat pumps can be attractive where:

- Water sources are limited

- Loads are variable

- You want modular, easy-to-install units.

Ground / Borehole Systems

Ground-source systems offer stable, year-round source temperatures, ideal for larger integrated schemes.

Surface Water (Rivers, Cooling Ponds, Seawater)

Where you have access to water bodies, you effectively have a giant heat buffer.

Sector-Specific Examples

Fermenter Cooling Circuits (Beer, Whisky, Biotech)

Cooling fermenters is a beautiful heat source for hot water:

- You’re removing heat gently over long periods.

- That heat can be reused for CIP or process hot water via a heat pump.

Pasteuriser Cooling Side (Product Being Cooled After Heating)

The cooling section of a pasteuriser can feed a heat pump that in turn supports the heating section or other hot water sinks.

Quench / Tempering Water in Metals / Glass / Ceramics

High-temperature product cooled rapidly in quench baths produces large flows of warm water – ideal sources.

Whitewater / Stock Cooling in Pulp & Paper

Whitewater cooling is another continuously available source, typically at moderate temperatures.

Matching Heat Sources to Heat Sinks – Practical Integration Ideas

You’ve now got a long shopping list of sources and sinks. How do you match them?

Classic “Fridge + Pasteuriser” Combo

- Source: Refrigeration condenser heat from cold storage or product chilling.

- Sink: Pasteuriser hot water or general plant hot water.

Result: You move from paying to cool plus paying to heat to paying once to move heat.

Using Dryer Exhaust to Feed Hot Water Systems

- Source: Exhaust air from spray/belt/fluid bed dryers.

- Sink: CIP hot water, bottle washers, space heating.

This can dramatically reduce burner or boiler load.

Pairing Reactor Cooling with Wash-Water Heating

- Source: Cooling water from exothermic reactors.

- Sink: Reactor CIP hot water, vessel washing, tank cleaning systems.

You’re essentially recycling reaction heat into cleaning duties.

Screening, Prioritisation and “Quick-Win” Opportunities

Temperature Match Matrix

Create a simple table:

- Rows = heat sinks (with required temperature)

- Columns = heat sources (with available temperature)

Highlight where source temperature + realistic heat pump lift can reach the sink requirement.

Load Profile and Simultaneity

Ask:

- Are source and sink available at the same time?

- If not, can you use buffer tanks or thermal storage?

Continuous source + continuous sink = easiest project.

Batch + batch = still possible, but you’ll need smart design.

CAPEX, OPEX and Operational Complexity

Some projects save a lot of energy but are:

- Hard to control

- Difficult to integrate

- Vulnerable to fouling or contamination

Start with the simplest, cleanest, most accessible streams for your first project. Build confidence, then go after the more complex opportunities.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Ignoring Fouling and Contamination

Effluent, dryer exhaust, slurry streams – they all foul heat exchangers.

- Use plate-and-frame or scraped-surface exchangers where needed.

- Consider intermediate loops to keep the heat pump side clean.

Forgetting About Controls and Turndown

Heat pumps don’t like wild swings:

- Design control strategies for part-load operation.

- Use bypasses and buffer vessels to keep the heat pump in a stable operating window.

Underestimating Hydraulic and Pumping Impacts

New heat exchangers, buffer tanks and pipe runs mean:

- Extra pressure drops

- Potential need for new pumps or pump upgrades

Include pumping power in your calculations – it’s usually small compared to fuel savings, but it’s not zero.

Conclusion – Building a Heat Pump-Ready Site

Identifying heat sources and heat sinks for industrial heat pumps in the process industry isn’t about finding one magic stream – it’s about seeing the whole site as a connected energy system.

- Heat sinks: evaporators, distillation, dryers, pasteurisation, hot water, HVAC, reactors, boilers, fermentation, auxiliaries.

- Heat sources: refrigeration condensers, cooling water, compressors, condensers, warm effluents, utilities, air/gas streams, CHP, ambient and sector-specific cooling circuits.

Once you map these, rank them by temperature, load and practicality, and then start matching sources to sinks. That’s where industrial heat pumps shine – not as a bolt-on gadget, but as an integrated part of a smarter, lower-carbon process plant.

If you take the time to build that map properly, your first project won’t just cut fuel and emissions – it will open your eyes to a whole new way of thinking about heat.

FAQs

1. What is the first step in identifying heat pump opportunities on an industrial site?

Start by building a simple energy map:

- List all major heat sinks (steam and hot water users) with temperatures and annual energy use.

- List all heat sources (cooled streams, condensers, effluents, exhausts) with temperatures and duty.

From there, look for temperature matches where a heat pump can reasonably lift heat from source to sink.

2. Which temperature range is most suitable for industrial heat pumps?

Most commercial industrial heat pumps:

- Take sources at around 10–40°C

- Deliver sinks at 60–90°C, with some high-temperature units reaching 100–120°C

Anything well outside this range is possible but gets more challenging and usually less efficient.

3. Can heat pumps fully replace boilers in process plants?

Sometimes, but not always. In many cases, heat pumps are best used to:

- Cover base-load heat at medium temperatures

- Preheat feeds and hot water

- Reduce overall steam consumption

Boilers often remain for peak loads and high-temperature or safety-critical duties. Over time, as confidence and technology improve, the heat pump share can grow.

4. How important is simultaneous availability of heat source and sink?

Very important for high efficiency. Ideally:

- Source and sink operate at the same time and similar load profiles.

If they don’t, you can still use buffer tanks or thermal storage, but the design becomes more complex and may increase CAPEX.

5. What kind of data do I need before talking to heat pump suppliers?

You’ll get far better proposals if you can provide:

- Process flow diagrams or P&IDs of key areas

- Temperatures, flowrates and duty profiles for candidate sources and sinks

- Existing steam, hot water and electricity costs

- Information on operating hours and seasonality

With that, you can move from vague “we want a heat pump” conversations to specific, bankable projects.

Ready to Unlock Heat Pump Opportunities on Your Site?

If you’d like support mapping heat sources and heat sinks, or want to test whether an industrial heat pump stacks up technically and financially for your plant, we can help.

- Site-wide heat & mass balance reviews

- Identification and ranking of viable heat pump integrations

- Concept design, CAPEX/OPEX assessment and decarbonisation roadmap

👉 Get in touch today to discuss your site, share a few key data points, and explore where a heat pump could replace steam, cut gas use and reduce your emissions