Why heating is the hardest part of industrial decarbonisation

Steam and hot water: the invisible backbone of production

If you run a process site, heat isn’t a “utility” – it’s the heartbeat. Steam and hot water quietly power the things that keep product moving and quality consistent: distillation, evaporation, sterilisation, Clean-In-Place (CIP), space heating, washdown, and all the little temperature nudges that stop a process from drifting out of spec.

The challenge is that heat demand in industry is messy. It’s not one tidy load. It’s often multiple loads, at different temperatures, starting and stopping across the day. And historically, the simplest way to feed that appetite was to burn fuel and make steam.

Now we’re in a different era. Carbon targets are tightening, energy costs swing like a pendulum, and sites are being asked to do more with less. That’s why decarbonising process heating has become one of the most important (and most misunderstood) parts of the net zero journey.

Why “just electrify it” is rarely that simple

Electrification is powerful, but it’s not magic. Think of it like switching from a petrol car to an EV: it’s not just the vehicle, it’s charging, route planning, peak demand, and infrastructure.

For a plant, “electrify heat” quickly turns into questions like:

- Can the grid connection handle it?

- What happens when everything starts at once on a Monday morning?

- Do we need HV upgrades, a new transformer, bigger switchgear?

- How do we keep resilience and uptime?

- Can we reduce heat demand first so the electrical upgrade doesn’t explode in cost?

This is where many projects either become brilliant… or become expensive science experiments. The good news is that there’s a practical path through it.

Start with the site, not the technology

Every plant has its own constraints

Two distilleries can look identical on paper and behave completely differently in real life. One has spare electrical capacity and plenty of low-grade waste heat. Another is landlocked for space, constrained by ageing distribution pipework, and already close to its maximum import capacity.

That’s why a decarbonisation strategy needs to be site-specific. If you start by picking the technology first (“we want a heat pump” or “we want an electric boiler”), you risk designing the solution around the idea, not around the plant.

What a good decarbonisation study actually looks like

A good study doesn’t just list options—it builds a defensible engineering case for the right options.

Data collection and heat mapping

This is where we separate real opportunities from “sounds good” ideas. We map heat sources and heat sinks, including:

- Flow rates and temperatures

- Time profiles (batch vs continuous)

- Seasonal variation (space heating can change everything)

- Existing control limitations and operational constraints

Build a baseline energy and carbon model

If you don’t know today’s truth, you can’t prove tomorrow’s benefits. A baseline model clarifies:

- Current steam generation efficiency and losses

- Distribution losses (often bigger than people expect)

- Hot water generation and recirculation behaviours

- Carbon footprint and cost drivers

Once you have this, the solution becomes less guesswork and more engineering.

Understanding your heat demand

Temperature levels matter more than people think

Not all heat is created equal. There’s a big difference between:

- 60–80°C hot water for washdown or space heating,

- 80–95°C for many CIP duties,

- 120–150°C for specific process heating,

- steam for high temperature duties and rapid heat transfer.

A lot of plants default to steam because it’s versatile. But if most of your demand is actually lower temperature, then using steam is like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut.

Batch vs continuous loads and why it changes everything

Batch loads (like CIP) create peaks. Peaks drive bigger boilers, bigger connections, bigger everything. If you can smooth peaks—using storage, sequencing, or pre-heating—you can often cut the “design maximum” dramatically. That’s a direct lever for lowering capex and making electrification viable.

Where your best heat sources are hiding

Refrigeration and cooling systems

Your refrigeration plant is basically a heat pump already—just running in the opposite direction. The heat it rejects to atmosphere can often be recovered. Condenser heat is frequently one of the most reliable sources because it’s steady and predictable.

Compressors, condensers and hot utilities

Air compressors reject heat. Vacuum systems reject heat. Even certain control cabinets and hydraulic systems reject heat (small individually, but meaningful at site scale if aggregated intelligently).

Waste heat from process and effluent streams

Warm effluent, product cooling loops, flash vapours—these are the “forgotten rivers” of energy on a site. With the right approach, they become feedstock for heat recovery.

High-temperature heat pumps: turning waste heat into useful heat

How heat pumps work (no jargon, promise)

A heat pump is like a “heat elevator”. It picks up heat from a low temperature source and lifts it up to a higher temperature where you can use it.

Instead of creating heat by burning fuel, it moves heat using electricity. That’s why it can be so efficient.

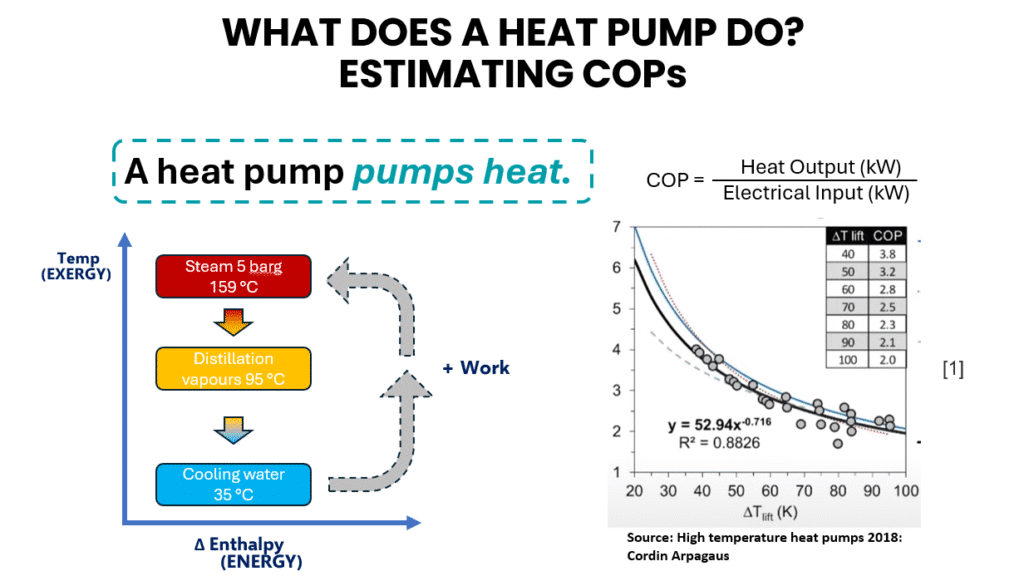

Typical COP ranges and what they mean for operating cost

Heat pumps are often described by COP (Coefficient of Performance). A COP of 3 means:

- You use 1 unit of electricity

- You deliver ~3 units of heat

That’s why heat pumps can reduce net energy consumption and carbon emissions—especially as electricity gets cleaner.

When heat pumps shine and when they struggle

Heat pumps shine when:

- You have a consistent heat source (like condenser heat)

- The temperature lift is reasonable

- Your heat sink can accept hot water (rather than needing steam)

Lift, temperature, and the “last 10°C problem”

The bigger the lift (difference between source and sink temperature), the harder the heat pump has to work. That last push to very high temperatures can be disproportionately expensive. This is one reason hybrid solutions are so attractive.

Heat pumps for industrial hot water and process duties

CIP and wash systems

CIP is often a perfect match for high-temperature hot water heat pumps. Why?

- Many CIP circuits are water-based

- Loads can be predictable with the right scheduling

- Pre-heating return streams can reduce steam usage significantly

Space heating and LTHW/MTHW networks

Space heating might not feel “industrial”, but on many sites it’s a meaningful year-round load. If you can feed a low/medium temperature heating network with a heat pump, you free up steam capacity and reduce boiler firing.

Pre-heating for distillation, evaporation and separation

Even if your process ultimately needs steam, you can often pre-heat feeds using hot water or recovered heat. That reduces steam duty—meaning a smaller electric boiler (or less electrical upgrade) later.

What about steam-generating heat pumps?

Why steam is tougher than hot water

Steam isn’t just “hot water at a higher temperature”. It involves phase change and pressure, and the temperatures can jump fast. That makes steam generation via heat pumps more complex, and in many cases the technology is still emerging compared to hot water systems.

Where the technology is heading

Steam heat pumps are developing, and we’re seeing more interest and pilot applications. But for many plants today, the fastest practical route is:

- Use proven hot water heat pumps where they fit,

- Then cover remaining steam demand with electric boilers.

Electric boilers: fast route to low-carbon steam

What electric boilers do well

Electric boilers are simple in principle:

- Electricity in, steam out

- High controllability

- No combustion, no flue gas, and often lower maintenance

If your electricity supply is low carbon (and increasingly it is), electric boilers can deliver a rapid emissions reduction.

Key constraints: grid capacity and electrical infrastructure

This is the catch. Electric boilers can demand serious power.

HV/LV upgrades, transformers, switchgear and protection

It’s not just “install the boiler”. You may need:

- Upgraded transformers

- New HV switchgear

- Cable routes and containment

- Protection coordination studies

- Power quality checks

Demand peaks and standing charges

Electricity costs can be heavily influenced by peak demand. If your steam system spikes, that can translate into higher demand charges. That’s why demand reduction and smoothing strategies can be as valuable as the technology itself.

The hybrid approach: heat pumps + electric boilers

Reduce steam demand first, then electrify what’s left

This is the approach we see delivering the best balance of carbon savings, practicality, and cost.

Heat pumps tackle:

- Hot water duties

- Pre-heating

- Heat recovery from waste streams

Electric boilers then provide:

- Steam for remaining high-temperature duties

- Fast response where needed

- Clean “top-up” energy

The “two-tool toolbox” that improves business cases

Think of it like renovating a house:

- Insulate first (reduce demand),

- Then upgrade the heating system (electrify efficiently).

Heat pumps improve efficiency. Electric boilers provide coverage and simplicity. Together, they reduce both carbon and the required scale of electrical upgrades.

Integration details that make or break a project

Pinch thinking without the headache

You don’t need a textbook pinch analysis to benefit from pinch thinking. The principle is simple:

- Use the lowest-grade heat for the lowest temperature loads,

- Save high-grade heat for where it’s truly needed.

Controls, turndown and operating philosophy

If controls aren’t designed properly, heat recovery systems get bypassed. The plant keeps running, but the savings vanish. Good integration means:

- Clear operating modes

- Automatic sequencing

- Practical overrides that don’t sabotage performance

Footprint, noise, maintenance and access

Heat pumps aren’t “install and forget”. They need:

- Access for maintenance

- Space for ancillary equipment

- Consideration of noise and vibration

- Correct water quality management

Economics: making decarbonisation financially viable

CAPEX vs OPEX and where the sweet spot usually sits

Some sites chase capex-only decisions and end up with high operating costs. Others chase efficiency and overcomplicate. The best projects usually:

- Target the biggest, most stable loads first

- Deliver measurable savings early

- Build confidence for the next phase

Carbon intensity of electricity and how it changes the answer

As the grid decarbonises, electrification becomes increasingly attractive. But you still need to consider:

- Your tariff structure

- Your operating schedule

- Potential for on-site renewables or PPAs

Phasing projects to de-risk investment

A practical approach is often:

- Quick wins and heat recovery,

- Hot water heat pumps,

- Electric boiler for reduced steam demand,

- Optimisation and monitoring.

A practical roadmap for process plants

Step 1: Measure and map

Get the data. Confirm what’s real. Identify losses and constraints.

Step 2: Reduce and recover

Fix distribution losses. Recover obvious waste heat. Optimise controls.

Step 3: Electrify

Deploy heat pumps where there’s a strong match. Use electric boilers to cover remaining steam.

Step 4: Optimise and monitor

Install metering. Track performance. Fine-tune sequences. Lock in the savings.

How IDEA supports electrification and heat pump projects

Feasibility to FEED to delivery

At Integro Design Engineering Associates (IDEA) Ltd., we support sites through the full journey:

- Opportunity identification and feasibility

- Concept selection and business case development

- FEED and detailed design

- Integration planning and delivery support

- Commissioning guidance and performance verification

Independent, vendor-agnostic engineering

We’re not tied to one supplier or one technology. That means we can focus on what your site actually needs, not what fits a catalogue.

If you’re exploring electrification projects, whether that’s high-temperature heat pumps, electric boilers, or a hybrid solution, we can help you map the best route from “idea” to “implemented”.

Conclusion

Decarbonising process plant heating doesn’t have to be overwhelming. The trick is to stop looking for a single silver bullet and start building a practical, site-specific strategy. High-temperature hot water heat pumps can unlock big efficiency gains by recovering and upgrading waste heat. Electric boilers can then deliver low-carbon steam, especially once heat pumps have reduced the steam demand to a more manageable level. When you combine both technologies with solid engineering, sensible integration, and a phased roadmap, you get a solution that’s technically robust and economically credible.

Our team at Integro Design Engineering Associates (IDEA) Ltd. is currently engaged in exciting electrification and heat recovery projects. If you’d like to explore what’s possible for your site, get in touch – we’ll be happy to review opportunities and help you shape a decarbonisation strategy that fits your operations and your sustainability goals.

FAQs

1) Are high-temperature heat pumps suitable for all process plants?

Not always. They work best where there’s a stable waste heat source and a significant hot water demand. A site study is the quickest way to confirm suitability.

2) Can heat pumps replace steam boilers completely?

In many cases, heat pumps can reduce steam demand substantially, but full steam replacement is often challenging today. A hybrid approach (heat pumps + electric boilers) is commonly the most practical.

3) What is the biggest barrier to installing electric boilers?

Electrical infrastructure and grid capacity. Many sites need upgrades to transformers, switchgear, and cabling to support large electric boiler loads.

4) How do I know whether to prioritise a heat pump or an electric boiler first?

Start with heat mapping. If you can reduce steam demand by recovering heat into hot water duties, do that first—then size the electric boiler for the remaining steam demand.

5) What’s the fastest way to build a business case for decarbonising my site?

Develop a baseline energy model, map sources and sinks, shortlist options, and quantify capex, opex, and carbon impact. The business case becomes clear when it’s built on real site data.